* * * * * * *

|

| Minus the shirtfront diamond. |

A master of men who once had been called “Big Bill,” but now (and he loved it) “Boss,” he had a ruddy tint of prosperity, a handshake that always gripped too tight, and a bold laugh, deep and booming, that rumbled in his guts, shook his frame, pulsed others till the whole room quaked with mirth. In a good mood, his voice was plumed and downy and stroked you to his ends. When angry, he smashed his fist in his palm, iced you with his eye.

His office at 59 Duane Street, just north of City Hall, had a glazed glass door that announced in gold lettering WILLIAM M. TWEED, ATTORNEY-AT-LAW. His pal Judge Barnard had admitted him to the bar; he knew no law. But the railings were nicked, and the doorknobs smoothed, by visitors who tapped his wisdom or besieged him with requests. Within a few busy minutes one morning he might patch up a quarrel between two aldermen; approve a contract for plastering the new county courthouse; and with a stroke of a pen create a deputy tax commissioner, a distributor of corporation ordinances, and an inspector of weights and measures – smokers of expensive cigars who thereafter would each be seen often amid the black walnut furnishings of Tammany Hall, but rarely on the job.

| A ball at Tammany Hall on January 9, 1860, to commemorate the 1815 battle of New Orleans. Too genteel and formal to be one of the Tammany balls where Tweed's double shuffle was a hit. |

To that same office came Councilman Hinkidink O’Toole, complaining that a court clerkship he wanted for his son had gone to Jim “Maneater” Cusick, a burly graduate of Sing Sing. Tweed consoled him: “C’mon, Hinkidink, shake off that blue funk. As street commissioner I can pave streets in your district.” Then, engagingly, putting an arm around the man’s slumped shoulders: “How about a new sewer?” Grudgingly, Hinkidink brightened.

| Ticket for an Engine Company No. 6 soirée at Niblo's Saloon, 1859. |

City Comptroller Slippery Dick Connolly, a jovial, clean-shaven ward boss, dropped by once to announce that Peter “Brains” Sweeny, the city chamberlain, known to his friends as Squire, was forfeiting votes because he couldn’t smile. “For one whole evenin’, Boss, I slapped him on the back till he was sore, shook his hand till his fingers and mine too ached, and made him smile and smile till every muscle in his mouth was twitchin’. ‘That’s it, Squire,’ I told him. ‘Go out among the lads like that, and you’ll be a roarin’ success.’ No use: he went out glum as ever. He’ll cost us a deal o’ votes.”

“Well Dick,” said Tweed, “he’s not called ‘Brains’ for nothing. No glad-hander, but in his quiet way he gets things done. Twists a lot of arms in corridors.”

|

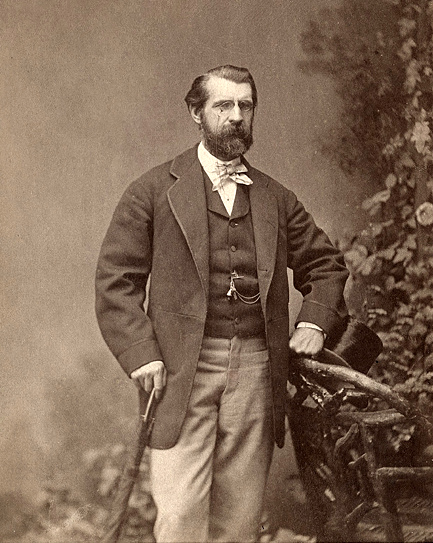

A. Oakey Hall, mayor of New York 1869-72.

This photo gives only a hint of his elegance.

The pince-nez were characteristic of the man.

|

“Now Peter,” said the Boss, “I know he wears velvet collars and embroidered vests, and cufflinks that he designs himself, but he’s our bridge to the bluebloods, gets invited into fancy parlors where we can’t set foot and maybe wouldn’t want to. Oakey’s all right; all he needs is ballast. He’d make a damn good mayor.”

In the realm of power the Boss knew everyone: Commodore Vanderbilt, who conferred with him about railroad rights of way; Justice George G. Barnard, Tammany’s brandy-sipping beau ideal of the bench; mayors and ex-mayors; governors and ex-governors; and toward election time assorted gang leaders and thugs, including Pegleg Gordon, who in scuffles at polls unscrewed his leg and swung. Consulting, smiling, joking with them, he retained every name, every face. To all he pledged, “My word is my bond,” and meant it. Greeted by him, not one of them forgot his clear blue eye, his gentle, crushing hand.

A carpetbag of the 1860s. Associated with Northern

adventurers in the post-Civil War South, but common

throughout the North as well.

Sobebunny |

Seeing how power nested in Albany, the Boss got himself elected state senator. At the start of each legislative session he traveled there on the Hudson River Railroad's special 10:30 a.m. express in a palace railroad car, leaving his private compartment at intervals to greet Sweeny and Connolly and the boys, who were playing poker in a series of smoke-filled parlor cars, their carpetbags stacked nearby. Twice each trip he walked the full length of the train, knowing that a first-name greeting and a handshake could bring joy to a Tammany man’s heart.

In Albany he held forth in a seven-room suite in the Delavan House, keeping two inner rooms for himself, guarded by sturdy doorkeepers, and the other five accessible to callers, who marveled at potted palms, at porcelain cuspidors festooned with painted roses, and sideboards offering decanters of whiskey, brandy, and gin. There he might keep a powerful Republican senator waiting in an outer room two or three days, while attending to the needs of “Oofty Gooft” Phillips, a water register clerk turned journalist, or other lowly Tammany suppliants. Yet small-time Republicans from upstate rural districts, desperate for a bridge repair or the dredging of a waterway on which their reelection depended, were welcomed with a smile: “Don’t worry, Nat, your project’ll go through.” Meanwhile, in quiet moments in an inner room, he and Sweeny scanned every bill up before the legislature, lest they include some hidden grant of property or power for which the price had not been paid. Observers might well wonder where true power lay – in the governor’s office at the capitol, or among the cuspidors and cut-glass decanters of a certain suite in the Delavan House.

Rarely seen with his hearth-clinging wife, whom he had lodged in a palatial Fifth Avenue brownstone, the Boss dined out often with cronies. When he hobnobbed at the upper end of the social scale, his speech was trimmed and neat; toward the lower end, it grew weedy with ain’ts. Joining in every toast at Tammany banquets, he barely sipped his wine, let others get drunk. At Tammany balls he led the boys, all of them spruced up in blue coats with brass buttons, in a grand march around the hall with their ladies while the band played “Hail to the Chief,” then frisked with a series of partners in a polka or mazurka, his huge frame surprisingly agile, his double shuffle the hit of the night. He was ravenous at clambakes, where juices dripped from his beard, but just as often, donning a pleated shirt with pearl buttons, he dined with the Elegant Oakey at Delmonico’s, where after a creamy potage and lobster in mayonnaise, he savored the crackle of woodcock as he crunched through delicate bones.

The son of a chairmaker of the Seventh Ward on the Lower East Side, he had come far, at last had money to burn. With a heart as big as a courthouse he gave to Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and to hospitals, orphanages, the poor in winter, and one-legged veterans of Gettysburg hawking shoelaces from wooden trays on the street. “Give,” he told his cronies, “always give.”

When reformers stiff in starched collars suggested that he had given too much to too many, that his marble company, printing company, and stationery company had milked the city of millions, he bristled. At the William M. Tweed Club of the Seventh Ward, where weary manure inspectors and assistant health wardens could relax at billiards and brandy, he told the assembled members: “Them croakers got scrubbed fingernails and shiny boots, they holds their nose and preaches. They ain’t never gonna know this city. It sprawls, it stinks. The streets is horseshit. But there’s more life in one sweaty block of tenements in this old Seventh Ward than in all their brownstones together. I love this city – it’s my steak, gristle and all!”

The club members mounted three rousing cheers for the Boss that rattled the grand piano and bounced off the bronze chandeliers. The next night, in a white waistcoat, he might dine with Judge Barnard amid the damasked elegance of Delmonico’s on truffled quail.

Rarely seen with his hearth-clinging wife, whom he had lodged in a palatial Fifth Avenue brownstone, the Boss dined out often with cronies. When he hobnobbed at the upper end of the social scale, his speech was trimmed and neat; toward the lower end, it grew weedy with ain’ts. Joining in every toast at Tammany banquets, he barely sipped his wine, let others get drunk. At Tammany balls he led the boys, all of them spruced up in blue coats with brass buttons, in a grand march around the hall with their ladies while the band played “Hail to the Chief,” then frisked with a series of partners in a polka or mazurka, his huge frame surprisingly agile, his double shuffle the hit of the night. He was ravenous at clambakes, where juices dripped from his beard, but just as often, donning a pleated shirt with pearl buttons, he dined with the Elegant Oakey at Delmonico’s, where after a creamy potage and lobster in mayonnaise, he savored the crackle of woodcock as he crunched through delicate bones.

The son of a chairmaker of the Seventh Ward on the Lower East Side, he had come far, at last had money to burn. With a heart as big as a courthouse he gave to Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and to hospitals, orphanages, the poor in winter, and one-legged veterans of Gettysburg hawking shoelaces from wooden trays on the street. “Give,” he told his cronies, “always give.”

When reformers stiff in starched collars suggested that he had given too much to too many, that his marble company, printing company, and stationery company had milked the city of millions, he bristled. At the William M. Tweed Club of the Seventh Ward, where weary manure inspectors and assistant health wardens could relax at billiards and brandy, he told the assembled members: “Them croakers got scrubbed fingernails and shiny boots, they holds their nose and preaches. They ain’t never gonna know this city. It sprawls, it stinks. The streets is horseshit. But there’s more life in one sweaty block of tenements in this old Seventh Ward than in all their brownstones together. I love this city – it’s my steak, gristle and all!”

The club members mounted three rousing cheers for the Boss that rattled the grand piano and bounced off the bronze chandeliers. The next night, in a white waistcoat, he might dine with Judge Barnard amid the damasked elegance of Delmonico’s on truffled quail.

| A Matthew Brady photograph of a painting of Tammany Hall members, early 1860s. The second seated figure to the right of the table looks very much like Tweed. |

In the 1868 elections he put District Attorney Hall up for mayor, Mayor Hoffman up for governor, and backed a score of other candidates as well; to elect them, Tammany mounted rallies and torchlight parades. As election day approached, Judge Barnard, white topper cocked at an angle while he sipped from a flask of brandy, naturalized up to nine hundred citizens a day by scrawling his initials on piles of blank applications. If witnesses to vouch for the applicants were lacking, he sent a bailiff to haul strangers in from the corridors and street. Thus certified, throng after throng of applicants took the oath intoned by the clerk, crowding round the only Bible in the courtroom, so packed together that each could barely graze it with a fingertip. “Vote early and often,” one veteran repeater urged them. “First yer votes with a mustache an’ whiskers, then quick to the barber an’ off with the chin fringe. Vote agin, then off with the sideburns. Vote agin, then off with the mustache, so yer votes plain-faced at last. That’s four votes sure an’ simple.”

On election night, long before the results were final, men and boys were piling up tar barrels, fences, cellar doors, and even wooden Indians that cigar store owners had failed to secure, to make bonfires in the street. The Boss and his cronies watched with smiles as in street after street of the Seventh Ward the dancing flames licked skyward, while boys danced and howled, and men discharged pistols and rifles in the air. To no one’s surprise, all his men got in. Throughout the city a deep gloom settled over reformers in brownstones, while joy crackled in tenements and shanties. City and state were his; not even he knew how far his ambition might reach. There were even rumors that he hankered, at least in fantasy, to be named ambassador to the Court of Saint James, where he would bow graciously, though with republican simplicity, to Victoria Regina, Queen of England and soon-to-be Empress of India.

William Marcy Tweed, a humble son of the city, was a man for whom the world had opened like a split rind; he tasted of its juices.

City of Wonder: What is it about New York? In the last several days I have encountered two memorable encomiums of the city of New York. In the Sunday Review section of the New York Times (7/28/13) Jan Morris, a Welsh author and traveler who has been coming here annually since 1953, comments on how the city has and has not changed. When she first came here, it was the City That Never Sleeps, the Never-Finished City, the Wonder City. Its architecture was the most exciting, its culture the most vibrant, its banks the richest, its slang an influence on how people talked across half the world. On her first evening in New York, a waiter said to her, "Just ask, ask for anything you like. Listen, in this city there's nothing you can't have." Today, by way of contrast, the city is more modest, gentler, older, wiser, subtler. And yet, it is still the Never-Finished City, a concentration of buildings that she sees as a concentration of character. And she proclaims it the most decent of the great cities of today, its truest icon the Statue of Liberty, expressing the truest purpose of the city and the nation. All this, from a foreigner who lives, not in some foreign metropolis, but in Wales! To her, we should be deeply grateful.

The other praise came from a Facebook friend living in London, but who longs for her native New York. Since she has published photos showing her disporting blithely in the vales of Albion, I told her she was obviously having fun over there, proof that New York wasn't the center of the world. Her answer: "Baloney! How can any place replace the beauty of the thriving, exciting, exhilarating, creative, energetic, and diverse mind-blowing city like NY? Don't ya know once a New Yorker, always a New Yorker???" And in a second message she added, "Can't you see the grimace through my smile? What kind of New Yorker are you who can't see the pain of being away from one's soul home?" At which point I acknowledged she was a true New Yorker and there was peace between us.

I only hope this city can live up to the image its friends abroad have of it. Yes, it's special, very special. That's what this blog is all about.

Wienie update #2: Mayoral hopeful Anthony Weiner, he of the ongoing sexting scandal, is now besieged with demands that he abandon the race, but he persists. In the latest poll he has dropped from first to fourth place, with Mistress Quinn now again in the lead. (See Wienie Update in the previous post: #74, July 28, 2013). Meanwhile an unlikely alliance of business interests, women's groups, and labor unions have united in an effort to stop ex-Governor Eliot Spitzer, our other scandal-tainted candidate, in his bid to become city comptroller. The farce continues. (See Election Note in post #72, July 13, 2013.)

Coming soon: Next Sunday, How America Goes to War: 1861, New York (how we did it then and how we do it now). Wednesday, August 7: Thomas Nast and the Power of the Pen (how a clever cartoonist brought down the most powerful man in the city). In the offing: the Hercules of Parks, and Battling Bella and the Queen of Mean.

© 2013 Clifford Browder

© 2013 Clifford Browder

On election night, long before the results were final, men and boys were piling up tar barrels, fences, cellar doors, and even wooden Indians that cigar store owners had failed to secure, to make bonfires in the street. The Boss and his cronies watched with smiles as in street after street of the Seventh Ward the dancing flames licked skyward, while boys danced and howled, and men discharged pistols and rifles in the air. To no one’s surprise, all his men got in. Throughout the city a deep gloom settled over reformers in brownstones, while joy crackled in tenements and shanties. City and state were his; not even he knew how far his ambition might reach. There were even rumors that he hankered, at least in fantasy, to be named ambassador to the Court of Saint James, where he would bow graciously, though with republican simplicity, to Victoria Regina, Queen of England and soon-to-be Empress of India.

William Marcy Tweed, a humble son of the city, was a man for whom the world had opened like a split rind; he tasted of its juices.

City of Wonder: What is it about New York? In the last several days I have encountered two memorable encomiums of the city of New York. In the Sunday Review section of the New York Times (7/28/13) Jan Morris, a Welsh author and traveler who has been coming here annually since 1953, comments on how the city has and has not changed. When she first came here, it was the City That Never Sleeps, the Never-Finished City, the Wonder City. Its architecture was the most exciting, its culture the most vibrant, its banks the richest, its slang an influence on how people talked across half the world. On her first evening in New York, a waiter said to her, "Just ask, ask for anything you like. Listen, in this city there's nothing you can't have." Today, by way of contrast, the city is more modest, gentler, older, wiser, subtler. And yet, it is still the Never-Finished City, a concentration of buildings that she sees as a concentration of character. And she proclaims it the most decent of the great cities of today, its truest icon the Statue of Liberty, expressing the truest purpose of the city and the nation. All this, from a foreigner who lives, not in some foreign metropolis, but in Wales! To her, we should be deeply grateful.

The other praise came from a Facebook friend living in London, but who longs for her native New York. Since she has published photos showing her disporting blithely in the vales of Albion, I told her she was obviously having fun over there, proof that New York wasn't the center of the world. Her answer: "Baloney! How can any place replace the beauty of the thriving, exciting, exhilarating, creative, energetic, and diverse mind-blowing city like NY? Don't ya know once a New Yorker, always a New Yorker???" And in a second message she added, "Can't you see the grimace through my smile? What kind of New Yorker are you who can't see the pain of being away from one's soul home?" At which point I acknowledged she was a true New Yorker and there was peace between us.

I only hope this city can live up to the image its friends abroad have of it. Yes, it's special, very special. That's what this blog is all about.

Wienie update #2: Mayoral hopeful Anthony Weiner, he of the ongoing sexting scandal, is now besieged with demands that he abandon the race, but he persists. In the latest poll he has dropped from first to fourth place, with Mistress Quinn now again in the lead. (See Wienie Update in the previous post: #74, July 28, 2013). Meanwhile an unlikely alliance of business interests, women's groups, and labor unions have united in an effort to stop ex-Governor Eliot Spitzer, our other scandal-tainted candidate, in his bid to become city comptroller. The farce continues. (See Election Note in post #72, July 13, 2013.)

Coming soon: Next Sunday, How America Goes to War: 1861, New York (how we did it then and how we do it now). Wednesday, August 7: Thomas Nast and the Power of the Pen (how a clever cartoonist brought down the most powerful man in the city). In the offing: the Hercules of Parks, and Battling Bella and the Queen of Mean.

© 2013 Clifford Browder

© 2013 Clifford Browder