HUGE BIG NEWS: Yes, I still have a new book in the pipeline, details to come. Meanwhile, I continue to shamelessly hawk my other books in the BROWDERBOOKS section that follows Lady Liberty.

We take her for granted, but she wasn’t always there, and it wasn't easy getting her set up in the harbor to greet incoming passengers back before

travel by air. Here, in honor of the Fourth of July, is how

it happened.

|

| featherboa |

|

| Laboulaye |

The idea for the statue was the inspiration of a French

legal scholar and author, Edouard René de Laboulaye, who admired the American Constitution

and wanted to commemorate the federal government’s abolition of slavery. In 1865, when our Civil War ended, he

established a committee to raise funds to assist the slaves in their transition

to freedom, and hoped that France and America might collaborate in building a

bronze colossus honoring this act of liberation. This was under the Second Empire, whose

collapse in 1870 led Laboulaye and his friends to revive their somewhat

neglected project, offering to design, build, and pay for the statue, if

Americans would provide a suitable pedestal and location. In a time of monarchy, it would be a joint effort in the name of liberty by the two republics.

When Laboulaye’s associate the French sculptor Frédéric

Bartholdi came to this country to promote the idea, he decided that the ideal

location would be Bedloe’s Island, recently ceded by New York State to the

federal government for military purposes.

There it would greet every ship arriving in the harbor of this, the

nation’s busiest port. In 1877 both

President Ulysses S. Grant and his successor, Rutherford B. Hayes, authorized

the construction of a monument on the island.

|

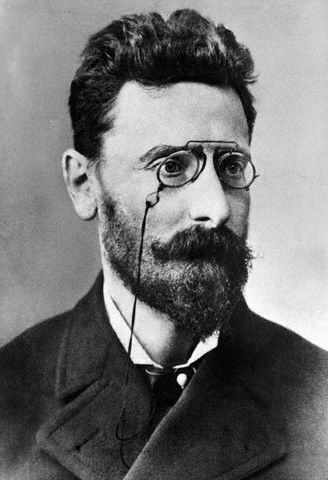

| Bartholdi in 1880, looking a bit Napoleonic. |

A done deal? Not at

all. Tired of sectional strife and

overwhelmed by a severe depression brought on by the Panic of 1873, white

Americans didn’t want to be reminded of the issues that had so recently and so

disastrously divided them; the North, in fact, was choosing to ignore the

proliferation of Jim Crow laws in the South.

Also, other states were reluctant to help finance a giant bronze female

that would grace the harbor of distant, oversized, and imperious New York,

while New Yorkers felt too pinched by hard times to spare the needed funds for

the massive granite base.

With this in mind, advocates now promoted the statue as a

memorial of the hundredth anniversary of American independence, and the time-honored

alliance of the French and American people.

Never underestimate the energy of a bunch of American boosters eager to

promote a project they fervently believe in.

The fund-raising committee published articles in the press, arranged

benefit performances of popular plays, and persuaded wealthy citizens to

exhibit their art collections and charge admission, the proceeds going to the

committee. At their suggestion,

Bartholdi sent the statue’s right hand and uplifted torch, so it could be

displayed at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876, an honor that

the Empire City grudgingly ceded to its perennial rival, the City of Brotherly

Love, since that was where the Declaration of Independence had been written

and approved. At the exhibition,

competing with Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, the Remington Typographic

Machine (i.e., typewriter), Heinz Ketchup, Hires Root Beer, and other

earth-shattering innovations, this fragment of Bartholdi’s colossus towered

above the mere mortals who were allowed, for fifty cents each (proceeds going

to the committee), to ascend a ladder to the observation platform just under the torch.

|

| At the Centennial, 1876, with the original torch (since replaced). |

|

| The head, on display at the Paris World's Fair, 1878. |

Even so, the campaign to raise the needed funds dragged on for years, and Laboulaye died in 1883. In December of that year the statue’s promoters held an auction for which they solicited artwork and literary manuscripts that would be assembled in a portfolio with a letter from President Chester A. Arthur and other items. Among those asked to submit a poem was 34-year-old Emma Lazarus, a writer who, though from a wealthy Jewish family, had done volunteer work to help the Jewish immigrants now flocking to the U.S. from eastern Europe. The result was a sonnet entitled “The New Colossus,” the closing lines of which would in time become famous:

Not like the brazen

giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs

astride from land to land;

Here at our

sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a

torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned

lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From

her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide

welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor

that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands,

your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips.

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses

yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of

your teeming shore.

Send these, the

homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside

the golden door!”

But the auction brought in only half the hoped-for amount,

and the poem was soon forgotten.

Political partisanship caused further delays, with Republicans at both

state and federal level allocating funds for the pedestal, only to be blocked

by Democrats. Packed away in over 200

crates in a European warehouse, the statue gathered dust; the French people,

having paid to have it cast, grew bitter; and Boston and Philadelphia promised

to build a pedestal at once, should the statue come to them. It was not New York’s finest hour.

The last-minute savior of the project proved to be Joseph

Pulitzer, the Hungarian-born publisher of one of New York City’s dailies, the New York World. Nothing pleased him more – or boosted

circulation more – than a crusade in print against monopolies, corruption, and

the misdeeds of the rich. Seeing the statue

as a gift from the common people of France to the common people of America, he

announced that what high-society fund raisers had failed to do in a decade, he

and the readers of the World would

accomplish in a matter of months. “The World is the people’s paper,” he

declared, “and it now appeals to the people to come forward and raise this

money.”

The last-minute savior of the project proved to be Joseph

Pulitzer, the Hungarian-born publisher of one of New York City’s dailies, the New York World. Nothing pleased him more – or boosted

circulation more – than a crusade in print against monopolies, corruption, and

the misdeeds of the rich. Seeing the statue

as a gift from the common people of France to the common people of America, he

announced that what high-society fund raisers had failed to do in a decade, he

and the readers of the World would

accomplish in a matter of months. “The World is the people’s paper,” he

declared, “and it now appeals to the people to come forward and raise this

money.”

Pulitzer’s journalistic instincts were sound: money poured

in -- pennies, dimes, and quarters – and circulation soared. Organizers ordered work on the pedestal to

resume, and when the crates with the statue arrived in New York harbor on June 17,

1885, the yet-to-be-assembled statue was greeted with the greatest

excitement. On August 11 Pulitzer

announced that the donations had reached the astonishing total of

$100,000. When the assembled statue, reinforced by an interior support structure of iron, was

dedicated by President Grover Cleveland and unveiled by Bartholdi on October

28, 1886, none of the speeches by dignitaries mentioned immigrants. But from then on, incoming vessels crammed

with immigrants fleeing inequality and oppression in Europe began viewing the

Lady as a symbol of the liberty they hoped to enjoy in America.

|

| The assembled statue in Paris, 1884. It was then taken apart, shipped across the Atlantic, and reassembled here. |

Viewing the statue from a distance, as most of us do, we may

miss some significant details. The pedestal, a truncated pyramid, has classical touches, including Doric portals. But who looks at that? It's the statue on the pedestal that catches the eye. If the

right hand holds aloft a torch that lights the world, the left hand clasps a tablet

inscribed in Roman numerals with the date July 4, 1776. Invisible unless seen close up, at the

statue’s feet lies a broken chain half hidden by her robe – a discreet allusion

to emancipation. And those seven spikes

radiating from her head? Rays from her

crown, representing the sun, the seven seas, and the seven continents. Modeled on the Roman goddess Libertas, the

Lady radiates classical gravity and dignity, and not the fury and violence of the French

Revolution, as shown in Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People (1830, another year of revolution), where the bare-breasted Liberty leads an armed mob over the

bodies of the fallen -- just the kind of violence that prompted Tennyson, a good English conservative, to deplore "the red fool-fury of the Seine." Bartholdi and his

friends believed in freedom and democracy, but not in revolution and

violence. And his Lady has worn well,

surviving the political partisanship that might have dethroned a more

controversial figure. Many a time,

returning on a late summer afternoon from a hike in the Staten Island

Greenbelt, I have seen Americans and foreigners alike flock to one side of the

ferry to view the statue and take the requisite photographs. Bartholdi’s Lady has indeed become a symbol

of both the city and the nation and what, at their best, they stand for.

|

| Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People (1830). Impressive, but not what Bartholdi had in mind. |

Sadly, Emma Lazarus did not live to see the triumph of the statue and recognition of her sonnet, for she died of cancer in 1887. Americans who were not recent immigrants were slow in seeing the statue as welcoming immigrants to the land of freedom. Only in 1903 did they place a bronze tablet inside the entrance to the statue’s pedestal bearing her now-famous lines.

|

| At sunset, December 2002. Geographer |

(A footnote: Jealous

little New Jersey, always resentful of the Empire State, has presumed to lay

claim to Bedloe’s [now Liberty] Island and, by extension, to the Statue of

Liberty, a claim that I, as a dedicated New Yorker and patriotic American,

reject with scorn. Those incoming hordes

of immigrants didn’t dream of New Jersey as their goal – did they even know it

existed? No, they dreamed of New York

City as the gateway to the land of liberty.

And so, New Jersey, hands off our colossus! Send us your mosquitoes, if you must, and the

stink of your marshes and oilfields, but leave our Lady alone.)

Source note: For

information on Emma Lazarus and the building of the statue, I am especially indebted

to Tyler Anbinder, City of Dreams: The

400-Year Epic History of Immigrant New York (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,

2016), an impressive and masterful account of the role of immigrants in the

history of New York City.

BROWDERBOOKS

All books are available online as indicated, or from the author.

If you love the city (or hate it), this may be the book for you. An award winner, it sold well at BookCon 2017.

No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World (Mill City Press, 2015). Winner of the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. All about anything and everything New York: alcoholics, abortionists, greenmarkets, Occupy Wall Street, the Gay Pride Parade, my mugging in Central Park, peyote visions, and an artist who made art of a blackened human toe. In her Reader Views review, Sheri Hoyte called it "a delightful treasure chest full of short stories about New York City."

If you love the city (or hate it), this may be the book for you. An award winner, it sold well at BookCon 2017.

|

Bill Hope: His Story (Anaphora Literary Press, 2017), the second novel in the Metropolis series. New York City, 1870s: From his cell in the gloomy prison known as the Tombs, young Bill Hope spills out in a torrent of words the story of his career as a pickpocket and shoplifter; his brutal treatment at Sing Sing and escape from another prison in a coffin; his forays into brownstones and polite society; and his sojourn among the “loonies” in a madhouse, from which he emerges to face betrayal and death threats, and possible involvement in a murder. Driving him throughout is a fierce desire for better, a persistent and undying hope.

For readers who like historical fiction and a fast-moving story.

For readers who like historical fiction and a fast-moving story.

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), the first novel in the Metropolis series, tells the story of a respectably raised young man who chooses to become a male prostitute in late 1860s New York and falls in love with his most difficult client.

What was the gay scene like in nineteenth-century New York? Gay romance, if you like, but no porn (I don't do porn). Women have read it and reviewed it. (The cover illustration doesn't hurt.)

For Goodreads reviews, go here. Likewise available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

What was the gay scene like in nineteenth-century New York? Gay romance, if you like, but no porn (I don't do porn). Women have read it and reviewed it. (The cover illustration doesn't hurt.)

For Goodreads reviews, go here. Likewise available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Coming soon: The Waldorf Astoria and the End of an Era.

© 2017

Clifford Browder